Ireland In The 1930s - 1940s

Foley's Dwelling, Muckross Traditional Farms.

The Political Scene - A Brief Sketch

The Irish Free State came into being at the end of 1922, following the signing of a Treaty with England in December 1921. This Treaty granted dominion status within the British Empire to 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland. It brought to an end the War of Independence, which had commenced against the British in 1919. Then followed a bitter and traumatic Civil War, between those who supported and those who opposed the Treaty. The Civil War lasted until May 1923. The anti-Treaty faction opposed the Treaty on the grounds that it did not grant full Irish Independence.

The Cumann na nGaedheal party, under the leadership of William Cosgrave, ruled the new state for ten years from 1922. This party was conservative in outlook and concentrated on consolidating the country's economy and its institutions. The party ruled largely without opposition until 1927. The previous year, Eamon de Valera had founded a new party, called Fianna Fáil. De Valera had led the opposition to the Treaty and had fought against the Government forces during the Civil War. His party won 44 seats in the general election of 1927.

William T. Cosgrave

Eamon de Valera

When Cosgrave called an election early in 1932. Fianna Fáil won 72 seats. They formed a Government with the help of the Labour Party. De Valera served as President of the Council of the League of Nations in 1932 and later as President of the Assembly. Fianna Fáil remained in power during the years of the Second World War, in which Ireland remained neutral. The war years were known as the 'Emergency' in Ireland. In the general election of 1944 Fianna Fáil once again were returned to power. However, they were defeated in early 1948 and an 'inter-party' or coalition Government was formed of several parties, under the leadership of John A. Costello. On Easter Monday, 1949, the 26 counties of Ireland became a Republic.

Agriculture

Irish Independent. Saturday, January 17, 1930

Ireland in the early twentieth century was a poor country. The levels of poverty in many isolated rural areas were exceptional by western standards. In 1930, the total population was just under three million. The great majority of the people were living in the countryside, or in country towns and villages. Dublin, the capital city, had a maximum population of about half a million people.

In 1930, the majority of Ireland's population occupied small agricultural holdings. Over a period of about 40 years, from the end of the First World War (1918), there was a general movement towards a consolidation in farm size. By the mid 1950s, forty-five per cent of farms were in the range of 30 to 100 acres. The total area occupied by both tillage and pasture in the 26 counties, in 1930, amounted to about 11 million acres.

Pasture was dominant, while the cultivation of grain continued to fall as it had since the Great Famine of the 1840s. Just over a million acres of grain crops were grown in 1921, this had fallen to just over 750,000 acres by 1931. In January 1930, the Honorary Secretary of the Irish Grain Growers Association appealed to Irish farmers to maintain at least the 1929 acreage of grain crops. The American economy had collapsed in 1929 and was succeeded by a worldwide depression. Irish farmers had received a poor return for their 1929 crop. Indeed, in many cases, they had found it difficult to secure a market for it.

Drawing home the hay for winter feed, West Kerry

Milking the cow

The number of cattle declined in the country from 4.4 million in 1921 to just over 4 million in 1931. Milch cows accounted for three quarters of these. The number of horses also declined slightly during this decade. However, at the same time, pigs and poultry experienced a sharp increase in numbers. The number of poultry rose by almost six million between 1921 and 1931. Between 1926 and 1936 the total number of men and women employed in agriculture fell from just over 644,000 to just over 605,000. This trend later accelerated, partly due to increased emigration during the Second World War (the Emergency). Wages were low for a farm labourer; earnings could amount to less than 15 shillings a week.

During the war years, the area of land under tillage rose dramatically. In 1939 the total area of tillage (including grain, root and green crops and flax) amounted to 1.5 million acres. This had increased five years later to 2.6 million. Wheat production rose dramatically but this did not prevent the introduction of bread-rationing in 1942. Tea, sugar and butter were also rationed. Meat remained plentiful.

Making sheaves of oats

Horse-drawn transport

Private motoring almost completely ceased in 1943 and gas and electricity supplies were drastically cut. The export of live cattle and meat products continued to form the basis of the export trade between Ireland to Britain. The summer of 1946 was one of the wettest on record and the wheat harvest was meagre. Bread rationing was, once more, introduced. In addition, there followed a particularly hard winter, fuel supplies were scarce and in early 1947 transport and industry almost ground to a halt.

Home & Family Life

Within rural Ireland there was a pattern of late marriages and a very high birth-rate within marriage. The rate of emigration, especially for single women, remained high during the 1930s and 1940s, with England the main destination. There was also a movement into urban centres from rural areas. By the 1940s it appears that a general discontent with their conditions was becoming evident among the rural population.

Family group, possibly West Kerry

Cooking over the open fire

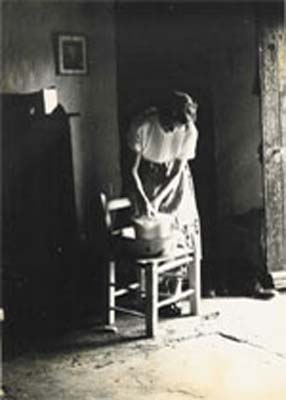

Woman washing clothes

On the family farm, the woman of the house was usually responsible for the care of the small livestock, the poultry, pigs and calves. She would also attend to the vegetable garden and to the growing of fruit. Usually there was no running water or electricity, sanitation was poor and there were few modern conveniences. Few women worked outside of the home and they usually lost their jobs on marriage. For instance, women teachers, who qualified after the 1st January 1933, were obliged to retire when they married. From the early 1940s on, sympathy was growing for the woman in the home and the difficult conditions under which she had to labour.

Tentative suggestions had been made, following the First World

War, for harnessing Ireland's abundant water supply for the

generation of electricity. In 1925 construction had commenced on

the main power station at Ardnacrusha, near Limerick. This was

completed late in 1929. In 1927 the Electricity Supply Board was

established. In the early years, electricity was provided mainly

to the towns and villages, by 1943 about ninety-five per cent of

urban populations had a supply. However, only about fifty per

cent of the population as a whole were connected to the network.

Obviously the instillation of electricity and the

provision of a water supply on tap were to have a dramatic

effect on the domestic scene. Comparisons, like the following,

were drawn between the lives of urban and rural women:

"Nowadays town houses are built for convenience

and labour saving, for comfort and economy in the running of

them. The townswoman has a supply of running water, a neat

range that will not burn much fuel and will supply hot water

to wash-basin and bath in the bathroom and to the wash-up

sink in the kitchen or scullery. She has hot and cold water,

good sanitation, electric light, a plug for her electric

iron, cupboard space and plenty of shelves. All this makes

heaven for the town home-maker. And all this goes for the

plain workman's wife as well as for the doctor's wife in

Merrion Square.

Irish Independent, Wednesday 15 January 1930

Irish Independent, Saturday 18 January 1930

The country woman then must drag in the cold water from

outside the house. For every basin of hot water she wants,

she must lift a heavy kettle on and off the fire. On

washing-day, washtubs must be filled and emptied time and

again; what it costs in labour to keep her churn and milk

vessels clean! The open fire-place in the country house

looks grand and when we think of the lovely cakes that come

out of the pot-oven, it makes us quite sentimental - but the

truth is that half the heat goes up the chimney with the

draught and the old pot-oven is unwieldy and clumsy and out

of date.

Now when night falls, the townswoman,

presses a button and at once there is a light and cheerful

glow about her. The countrywoman, like the Wise Virgin in

the gospel, has had to clean and tend and fill her lamp

before lighting it or else she has to depend on her

halfpenny dip. Millions have been spent on the Shannon

scheme but it is not the countrywoman who has the benefit of

it."

(Muintir na Tíre Official

Handbook, 1941).

Taken from 'Electrical & Sundries,' 1925-26 season

Taken from 'Electrical and Wireless Sundries,' 1925-26 season